Citizen Security and Social Media in Mexico’s Public Sphere

Research Compiled for the School of International Service

American University

Kristen Blandford, Rosemary D’Amour, Kathleen Leasor, Allison Terry, Isadora Vigier de Latour

Abstract

With the rise of drug-related violence in Mexico, Mexican citizens are using social media to warn fellow citizens and promote intra-national communication. This research focuses on the public sphere as it relates to selected social media platforms including Twitter, Facebook and blogs—appropriate platforms because social media is transforming the public sphere in Mexico, moving conversations from offline to online. The researchers do not focus on one single social or political movement. Instead, the focus is on the broader issue of citizen security in Mexico, how it is being discussed in the public sphere, and how this is changing the public sphere. With the increase in drug-related violence since 2006, people are obtaining and sharing information about citizen security in Mexico through information and communication technologies. Access to social media (Facebook, Twitter, blogs, etc.) is transforming the public sphere as various sectors (civil society, media and the government) figure out how to engage people and create niche networks on these various platforms. The decentralized nature of citizen security and disruptions in traditional communication channels are forcing citizens to seek information and discuss these issues online.

Key words: Drug violence, citizen security, social media networks, public sphere, Mexico

1.Introduction

This

report explores how social media is used as a new platform in

Mexico’s public sphere in order to fit their changing needs in

relation to citizen security, citizen security being defined as

narcotics trafficking related violence as it impacts citizens’

everyday lives. The research tries to answer a fundamental

question: how is Mexico’s security situation driving actors to use

social media platforms to find and share information about security

differently? The researchers have analyzed three different sets of

actors to answer this research question: civil society, government,

and media organizations, and followed their social media movements

online.

More

specifically, the researchers are studying how social media has

provided Mexican citizens a platform to discuss narco-related crime,

also known as the public sphere, a theoretical model widely argued by

Habermas and Hauser. Though Habermas' definition of the public sphere

is the foundation upon which the idea is discussed in prior research,

it is perhaps too rigid for the fluidity of discourse via social

media. Thus, Hauser's definition, which built upon Habermas and

relies heavily on the idea of reciprocity and engagement, is better

suited for both the medium and the message within Mexico's

narco-related citizen security context. This idea of social media as

a tool for civic, political, and journalistic engagement to report,

define, and combat narco-related crime is an evolving process within

Mexico, sparked by dissent and sustained by organization.

For data analysis, the researchers predominantly looked at the social media platforms Twitter, Facebook and blogs, but they also used alternative resources such as conducting qualitative interviews. For the civil society group, they analyzed two very different social media movements: Movimiento Por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad (Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity) and Blog del Narco (Drug Blog). For government, they analyzed how the government disseminates security information, and responds to the general public using social media to absolve issues of violence. For the mainstream media, they are comparing the use of hashtags such as #mtyfollow to report on violence and contribute to the conversation of a journalist group Periodistas de a Pie (Journalists on Foot), who are professional media journalists, which contribute to the public sphere. This analysis focuses on how and what information is shared on their Twitter network.

(i) Civil Society

The researchers chose Movimiento por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad (MPJD), led by Mexican poet Javier Sicilia, to illustrate how civil society groups in Mexico are raising awareness about narco-related crime in the public sphere; MPJD are by far one of the most popular and committed social movements fighting for peace and justice in Mexico today. They are dedicated to fighting for the mutual interests of the victims of the drug war creating peace, hope and change for a newer and safer Mexico—and are steadily using online social media platforms as tools to galvanize community action. For simplification purposes they can be looked upon as a case study of using online action to increase offline change in Mexico.

The researchers also chose to analyze the Blog del Narco because there are various aspects of Hauser’s public sphere on the blog that are pertinent to Mexico’s narco-related citizen security contexts. Namely, it is a discursive space in which individuals can associate to discuss matters of mutual interest related to the narco-crime in their communities. Since the authors can maintain anonymity, Mexican citizens are not afraid to report events happening in their neighborhood, creating overlapping interaction and consensus. Blogs similar to Blog del Narco are dramatically altering how Mexican citizens participate in the discussion of narco-related crime, transforming this online public sphere into a place of emotional discussion and dialogue. Anonymity assures that the individual will not be threatened to release information, nor can they be bribed, which assures citizens that they can voice their opinions and the “gatekeeper” will be transparent and accountable.

(ii) Media

The researchers chose Periodistas de a Pie (Journalists on Foot) as a case study for this project to provide insight on the media sector in Mexico. Periodistas de a Pie is an organization is a formal network for journalists, and it provides training in reporting strategy, freedom of information, and trauma response. Because journalists have been intimidated into silence and fear repercussions for their reporting, especially as it involves narco-related violence, their use of social media does not fully capture the potential for electronically-shared information and its capacity for transforming the public sphere. They are a case study of the potential for reporting and defining narco-related crime to inform the public, but also represent the effects of contextual obstacles to fully using these vectors.

(iii) Government

The Secretaría de Seguridad Pública (SSP, Public Safety Ministry) was selected as a representative case study for the government perspective on security as the organization was dispatched on the front line of the drug war from an early stage. The institution symbolizes Mexican citizens’ complicated relationship with an imperfect government in a concerning security environment, due to the SSP’s important role in domestic security issues and its concurrent involvement in human rights violations and corruption scandals. The researchers used data from the SSP’s Twitter network to analyze the discourse on the government’s role in security held by Mexican Twitter users. The SSP is a case study of ineffective use of social media to create a meaningful dialogue around security issues.

II. THEORY AND MODELS

This research tested how different actors in Mexican society are using social media platforms in response to security needs by analyzing their behavior through the Public Sphere model. Hauser’s rhetorical public sphere model is ideally suited for the stated research question, as it provides the researcher a structure with which to understand opinion and consensus-building in this space as a process by which publics form (public sphere). The public sphere offers a vantage point for understanding barriers to entry into the sphere, which is particularly pertinent in Mexico.

The public sphere, in general terms, is any space where private citizens come together to form a “public” in which ideas and information are exchanged (Habermas, 1989). Habermas’ (1989) foundational work examines the maturation of the public sphere into the political public sphere, characterized by rational and critical debate focused on the content under discussion, equality of participants, freedom to openly discuss any topic, freedom of assembly, freedom of expression, and the intention to reach consensus (quoted in Miller, 2011, p. 87). Discourse in the political public sphere influences political outcomes where successfully channeled. In contrast, Hauser (1999) argues that the core of public opinion formation centers on discourse in a rhetorical public sphere. Hauser’s public forums exist where active, interested individuals can organize around and develop a dialogue about issues. Contrary to Habermas’ rationale, political public sphere, arguments in the rhetorical public sphere are more likely to hold based on how well they resonate with the participants. While political action may result from the rhetorical public sphere, its principal output is shared awareness of common issues. Characteristics of the rhetorical public sphere include permeable boundaries, activity, contextualized language, believable appearance, and tolerance (Hauser, 1999, p. 77-80).

As Miller points out, the Internet, as well as other information and communication technologies (ICTs), shares many of the characteristics of these public sphere models – increased access to information about political developments, increased ability of people to produce political discussion, increased equality through anonymity, and very free expression and association (2011, p. 145). This research conceives of a public sphere centered on the issue of citizen security in Mexico, and is one specifically located in social media platforms online. The researchers will consider the citizen security-focused social media public sphere as a potential transformation of the public sphere, and examine whether its outputs more closely resemble those of the political public sphere (consensus to influence political outcomes), the rhetorical public sphere (raising awareness), or a new kind of output.

A valuable contribution of the public sphere model is the recognition of barriers to participation. Access barriers in the context of the Internet have readily been addressed through the concept of the “digital divide,” or the gap between those who can access the Internet and those who cannot, both physically and effectively (Miller, p. 98). This consideration is especially important to account for in social media research in Mexico, which has only a 30% Internet penetration rate (Telecom Paper, 2012), and in which the majority of social media users are concentrated in Mexico City (Ricaurte, 2012). While access to social media via mobile phones is increasing, physical Internet access, barring psychological and knowledge barriers to Internet use, is lowest in rural Mexico, where organized criminal groups are most active and the population has the greatest need of resources for citizen security (Farah, 2012). An important point to consider when examining social media’s role in public sphere formation is that social media only works for people who are active and interested. There are no disinterested parties using this technology, especially when the technology is difficult to come by, as in Mexico, where the majority of citizens have limited access to it. So, the spark of conversation is dissent: People are only talking when they have something to say.

III. METHODOLOGY

In order to understand the characteristics of the Mexico citizen security social media public sphere, the researchers gathered a variety of qualitative and quantitative data. Online data was collected primarily from blogs, Youtube videos, newspaper articles and the Twitter and Facebook accounts of the sectors that were focused on. All Twitter data was collected independently, with the help of open-source software to assist in automation of quantitative analytics (number of tweets, top tweeters, etc.). Online data focused on selected organizations/individuals deemed to be representative of each part of the public sphere – civil society, journalists, and government – on which our study tracked. Civil society was represented by the NGO Movimiento por la Paz and Blog del Narco. Journalists were represented by the journalist organization Periodistas de a Pie. Government was represented by the Secretaría de Seguridad Pública (SSP, Public Safety Ministry). An analysis of the #mtyfollow hashtag, used to warn citizens of Monterrey, NL, Mexico about possible security issues, was also undertaken to understand some of the more fluid developments in this public sphere. Offline data consisted of qualitative interviews and other research on the use of social media to spread information on security and citizen security initiatives in Mexico, as well as the context of the drug war.

The software tools used to analyze the network data and how information is disseminated in the public sphere include the Archivist[1] and NodeXL[2]. The Archivist uses information from specific Twitter handles or hashtags and creates visual representations of the relationships in this network. It also tracks data including the number of Tweets during a specific time period, top users in the discussion, the top content of the discussion, and the nature of how the data is created (i.e. Tweets vs. Retweets). Twitter analytics allow us to track trends, interests, the life cycle of news, and high volume tweeters within these networks, as well as a sampling of the social context within these networks are based in the twittersphere.

The second tool, NodeXL, used in conjunction with Microsoft Excel provides plug-ins that specifically targets the nature and fundamental information about Twitter handles and hashtags. The program, similar to the Archivist, creates visual representations of how information flows, and its consistency, between people and organizations in the network. Limits on the amount of data that can be pulled from Twitter meant that smaller networks (>5,000) were fully mapped, while larger networks were estimated with samples of randomly selected users in the network, generated by NodeXL.

The final tool utilized in our research is in-depth interviews, to supplement our data with qualitative research. Team members interviewed civil society members, journalists, researchers and a government official. Two interviews were done on the condition of anonymity to protect the identity of the persons, and one of those was done entirely through electronic means. The researcher followed suggested methods from a chapter in Christine Hine’s Virtual Methods (Orgad, 2005), building trust with the subject through respecting their right to privacy and anonymity. The other two were conducted face-to-face. These interviews are a critical aspect in providing contextual information on the security and information sharing situations in Mexico.

IV. DATA AND ANALYSIS

Social media has played a crucial role in the evolution of communication internationally--the immediacy and near democratization of information flows has enabled people to communicate both as private citizens, or in groups, and either between each other, or with those in power. How this has occurred within Mexico, however, is the focus of this report, relating specifically to the citizen security context within the country’s borders.

The social media presence in Mexico in itself mirrors the most crucial elements of the fight for citizen security. The drug war, and force exercised by cartels in Mexico, is decentralized, largely removed from the federal government. Most occurrences of corruption, coercion and intimidation towards government, media and individuals occurs outside of the formal power center of Mexico City, the country’s capital, and instead within state and local municipalities. Similarly, the technological diffusion within Mexico has followed a similar vein: An estimated 30% of Mexicans have Internet access, and the most prevalent social media use is also concentrated within the capital, as 60% of Twitter users are located in Mexico City (Ricaurte, 2012). This limited reach of an enabling tool has been an issue noted within data analysis on the government, civil society, and the media. The possible digital divide, and subsequent echo chamber of information circulating on platforms such as Twitter, or a “cyberintelligentsia” who dominate the discussion, mean a limited discussion and possibility for change of the citizen security context (Ricaurte, 2012). As the structure of the public sphere directly affects the quality of the discourse it produces (Hauser 1999), barriers to Internet access restrict a widening of observers in the space whose diversity could produce more widely applicable and more critically examined proposals for addressing security issues. A skewed discussion, perhaps by Mexico’s “cyberintelligentsia,” is likely to produce skewed solutions at best, or manipulate the discussion to suit their own ends at worst. While social media’s nonhierarchical qualities may at first glance seem to increase the permeability of boundaries in the space (one of Hauser’s five characteristics of a well-ordered rhetorical public sphere), its dependence on Internet infrastructure can also lessen its effectiveness as a dialectic medium.

IV.A – CIVIL SOCIETY

IV.A.1:

Movimiento por La Paz (MPJD)

When Javier Sicilia formed MPJD in March 2011 he was coming from a place of desperation, anger and emotional hardship following the brutal assassination of his son. His goals behind forming the movement lay within the idea of creating a space where the victims of the drug war could share, and exchange ideas to bring the issue of citizen security at the top of the political agenda with the hope of creating new anticrime strategies and reforms (Time magazine, December 2011). Quickly Sicilia and his movement learned that using social media platforms to raise awareness on Mexico’s security situation and alarm citizens of the “breakdown of the Mexican social fabric” (NYT, October 2011) would provide a safer public forum to bring peace justice and dignity to Mexico. MPJD’s use of social media demonstrates how the movement is using alternative platforms in Mexico’s public sphere to share and diffuse information differently. This section will analyze MPJD’s network analysis of social media use and content analysis referring to additional sources of information such as qualitative interviews our team conducted.

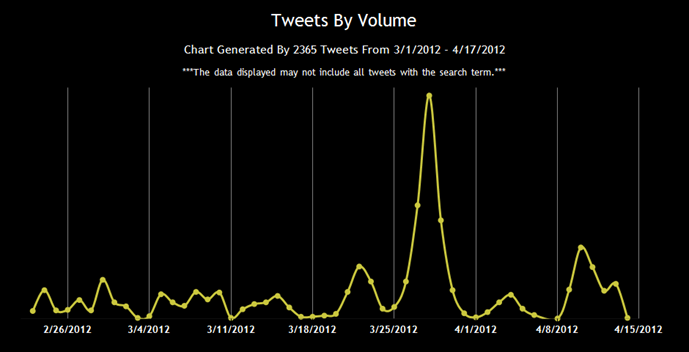

To analyze the data for Movimiento por la Paz the researchers used the Archivist software and focused on the tweet volume over a specific time period (March 1st - April 19th). The tweet results over this time demonstrated when the movement was actively tweeting or mentioned due to a particular event that took place. As shown in Appendix A (Figure A.1.1) an utmost peak was reached around March 28, which marked the one-year anniversary of the movement. The hashtag used at this time was #AniversarioMPJD. Tweets were being posted every 10-15 minutes! By actively analyzing MPJD’s Twitter feeds and Facebook posts the researchers have noticed that there usually tends to be more activity towards the end of the month. For instance, February 29, March 23 and 28. An increase in feeds and posts is usually related to reporting on x amount of people that were kidnapped or killed, advertising an upcoming event or march, or marking a major event such as the one year anniversary of the movement on March 28.

The use of qualitative interviews was very useful to further understand MPJD offline and online action. Our interview with professor Ricaurte (Ricaurte 2012), visiting scholar at the University of Maryland studying digital literacy and cyberactivism, was helpful to better understand the rise of social movements in response to the drug related violence and insecurity in Mexico. She provided us with some useful background information on Movimiento por Paz stressing their ideological and religious views and actions taken to bring a voice to the families of the victims. Her opinion of MPJD remains neutral, as although she honors their efforts, she is also realistic that if any change is to take place it needs to be done in collaboration with the local government. Another valuable primary source was our interview with Fred Rosen (Rosen, 2012) an independent journalist based in Mexico City. Rosen, who recently interviewed Javier Sicilia on three occasions, provided us with further insight on the movement, explaining their ideological views and background and how this reflects their actions today. He also elaborated on Sicilia's initial interaction with Calderon´s administration and current conversations with the government. This was very helpful to better understand the movement's relationship with the government as traditional media does not portray such information accurately.

IV.A.2: Blog del Narco

As of May 2012, the Blog del Narco Twitter account (@InfoNarco) did not follow any other users but hasd over 104,000 followers, including CNN Espanol, all major Mexican media outlets, the FBI, the Mexican Secretariat of National Defense. This illustrates just how influential the blog is across political and media environments. However, it is particularly important to political and media entities because has become significant to Mexico’s public sphere, and serves as a reflection of what Mexican citizens discuss about narco-related crime within their own communities but on an online platform. The amount of the account’s tweets vs. retweets is relatively equal, but based on percentages @InfoNarco makes more retweets (59.74%) than unique tweets (40.26%). These retweets come mainly from their followers, and the account does not retweet any other user’s content, rather the author posts events on what is occurring in various areas throughout Mexico based on the tips they receive from civil society members. The information that the blog receives is collected through an anonymous e-mail account hosted on the website. Based on the researcher’s first hand observations, Blog del Narco does not follow any other users because it makes it more difficult to find out where the information is coming from. One of the reasons why Blog del Narco has been so successful supplying information, and trusted by the Mexican public, is the citizen blogger’s ability to stay anonymous, and keep his or her sources unknown. Additionally, people have come to rely on the information that comes from the blog on learning about security issues.

Since the authors can maintain anonymity on Blog del Narco, Mexican citizens are not afraid to report events happening in their neighborhood, creating overlapping interaction and consensus pertinent to Hauser’s public sphere. Blogs similar to Blog del Narco are dramatically altering how Mexican citizens participate in the discussion of narco-related crime, transforming this online public sphere into a place of emotional discussion and dialogue. Anonymity ensures that the individual managing the blog will not be threatened to release information, nor can they be bribed, which assures citizens that they can voice their opinions and the “gatekeeper” will be transparent and accountable.

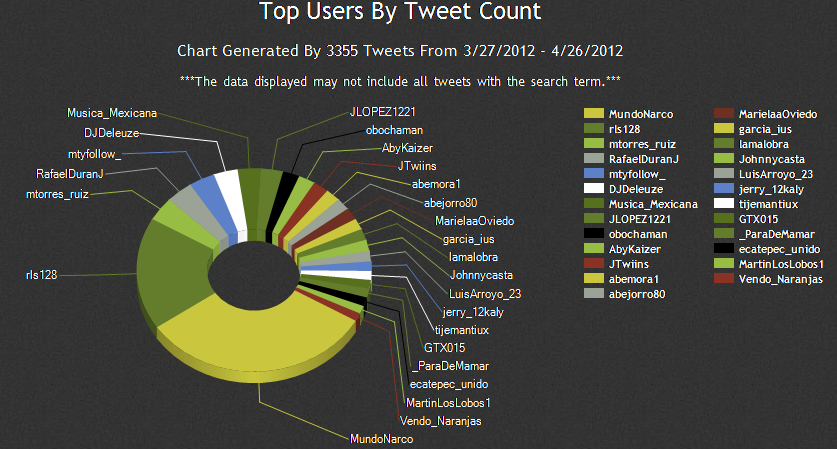

The researchers followed specific Twitter users to decipher trends within Mexico’s civil society, such as who specifically is engaging in this new online public sphere. For example, the user @rls128 is journalist named Ricardo, who discusses drug security related issue and re-tweets content provided by both the @MundoNarco and @InfoNarco accounts (see Appendix, Figure A.2.5). @RafaelDuranJ is a professor named Rafael Durán Juárez at the University in Sinaloa and a lawyer defending human rights. This user specifically follows and discusses drug related events affecting Nuevo Laredo. These users illustrate the broad ranges of interest, areas, and discussion in Mexican civil society about narco-related crime through social media. Although citizens may be in separate cities of Mexico, the Blog del Narco contributes to the public sphere because it creates overlapping interaction and consensus about narco-related crime. Blog del Narco is an online public space that encourages emotions and dialogue, and the followers and users resonate with the content because the subject matter discusses what is going on within their own communities.

IV.B – MEDIA

Today, Mexico’s media environment is changing, much like that of the rest of the world. Media organizations and journalists have to adapt to new information flows online, created by citizens’ needs for immediate information previously unachievable. Information is shared and disseminated through a variety of platforms in the online realm, and the buzzword for journalists today is social media. To stay competitive, journalists and media outlets have to take advantage of their position within a network, to remain the primary source of information diffusion. This means adapting to the immediacy of information flow. Seen in Hauser’s terms as information and thought leaders, this transformation of the public sphere presents a myriad of challenges for media, such as verifying information that is received online in order to report it as fact.

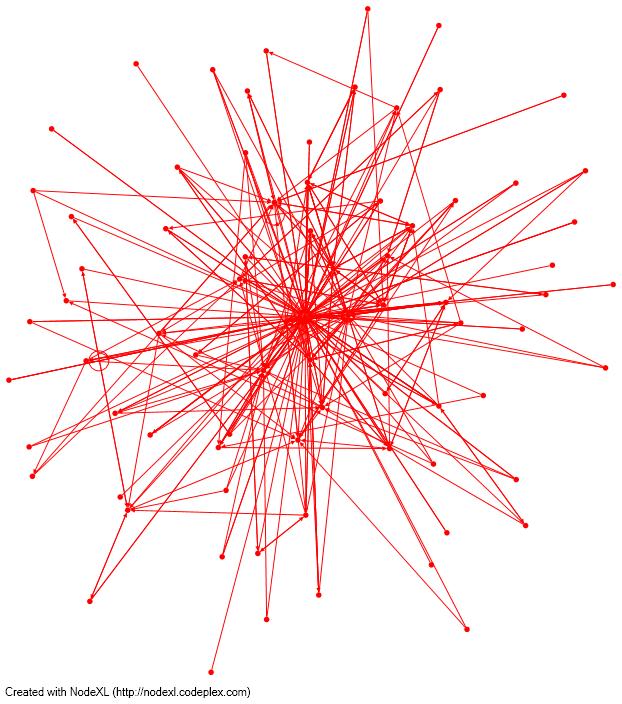

For this portion of data research, it’s helpful to visualize the way people communicate and the way information flows online, particularly through a Twitter network, representative of a new, evolving public sphere of knowledge. To create a visualization of this information flow, data is being analyzed using NodeXL, an online tool to graph and diagram Twitter networks.

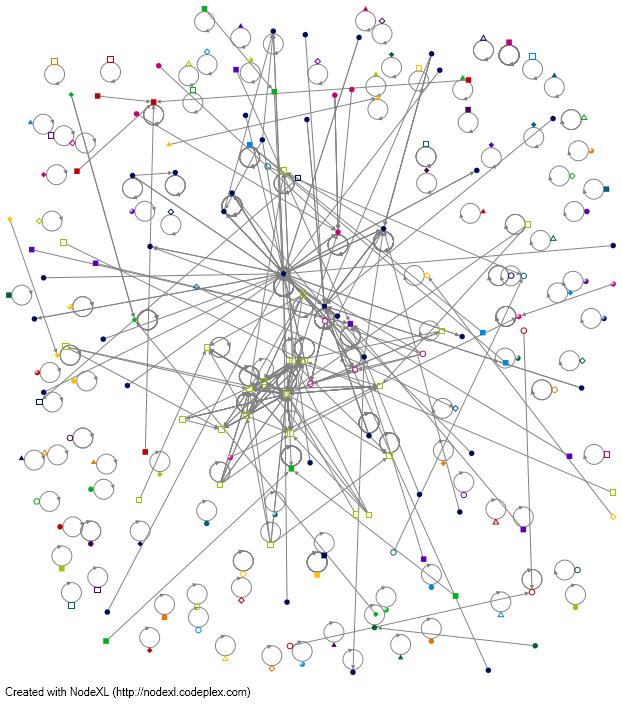

Individual users who follow hashtags, such as the common hashtag #mtyfollow (Appendix B.1.1), or “Monterrey Follow” in Mexico, are not bounded by the same network connections that are associated with user-to-user interaction. This is especially true for common hashtags, which can be used for a variety of reasons. For example, a generic hashtag designed merely to organize regional information, like #mtyfollow, or even #reynosafollow, etc., may contain information relevant to a variety of information that users seek online--be it news, entertainment, or security messages. The hashtag itself, therefore, connects users in theory, but does not necessarily result in an organized information flow because the type of information received is more varied. There is a much more sporadic connection within a network created by a hashtag, although again this depends upon the number of users and the reasoning behind the hashtag.

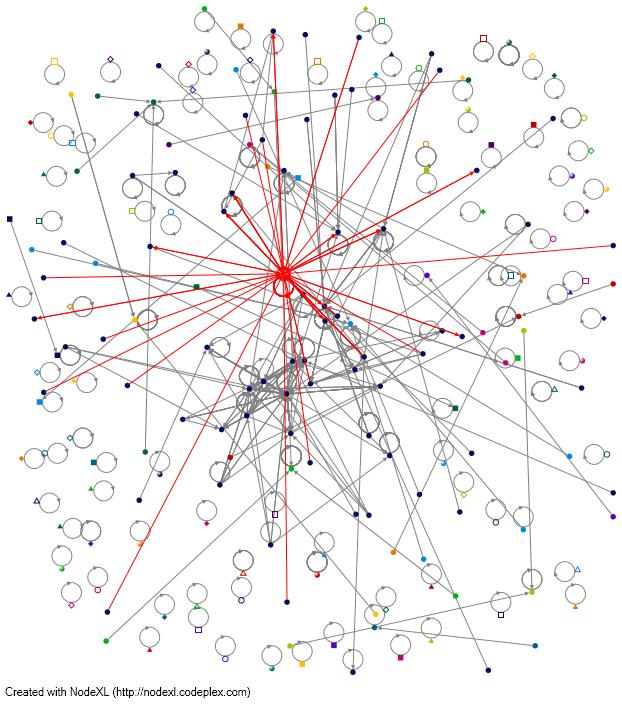

Individual users within a network, such as #mtyfollow, have limited immediate impact, merely because of their location within the network, and their individual clout. A sample user within the #mtyfollow network, @erikam (Appendix B.1.3), has potential to have his information on Twitter spread using the #mtyfollow hashtag, but several elements would have to fall into place in order for this to occur in a systematic way. A civil society group, such as CIC, or Centro de Integracion Ciudadana based in Monterrey, uses its social capital to disseminate security information on Twitter (Appendix B.1.2). As the graph indicates, their reach within the #mtyfollow network is more extensive than an individual user, and connects to more well connected users, meaning that if information were to originate with CIC, it could spread rapidly.

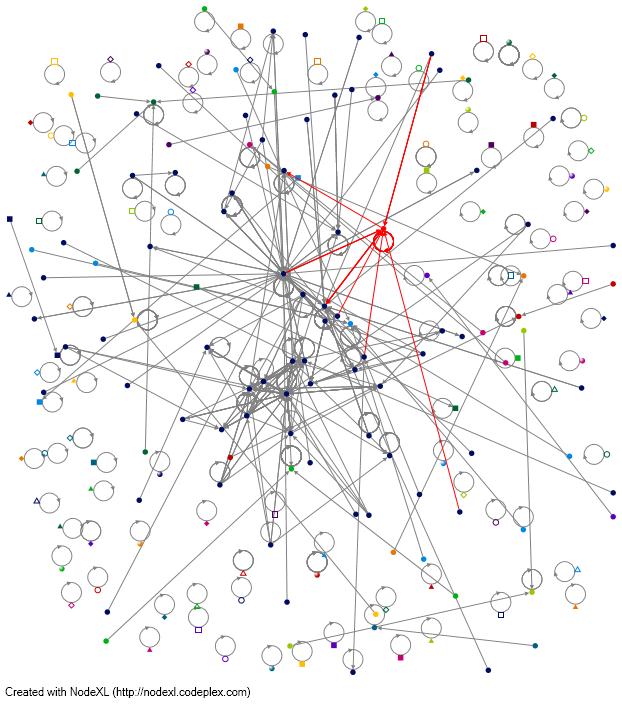

However, when media enters the online fray, the picture becomes a bit different. Media and journalism organizations often carry with them an established offline identity into the online realm, and their connectivity within the network trumps that of individual users. Media organizations and journalists are at an advantage in the early stages of social media for news because of their established identities as purveyors of information. Success in this realm seems to rely upon a two-way communication between the hub of a network, in this case, an organization of journalists, and this conversation is supported greatly by social media platforms. For an organization like Periodistas de a Pie, a collaboration of Mexican journalists, information diffusion is incredibly systematic (Appendix B.1.4). There is a three-step process by which users in the network receive information, represented in Appendices B.1.4 to B.1.7. First, news organizations disseminate information (Appendix B.1.5), then they engage with a conversation with their followers (Appendix B.1.6), and then users share that information with their followers, which results in a complete “information saturation” of the network (Appendix B.1.7).

The key comparative aspect of this research is the difference between individual users and established media networks. Users seeking information will head first to media organizations, established communicators, whereas individual users who may have information of importance within the network have incredible hurdles to overcome if they want to have the same effect as media organizations on Twitter. This idea is transformative when Mexico’s citizen security context is brought in to the discussion.

Because journalists have been intimidated into silence and fear repercussions for their reporting, especially as it involves drug-related violence, their use of social media does not fully capture the potential for electronically shared information and its capacity for transforming the public sphere. This research focuses on how journalists are using social media to communicate mostly amongst themselves about issues related to the support and safety of journalists in Mexico, playing into the idea of the public sphere as a gathering place for active, interested individuals and groups. This is illustrated by looking at the network analysis of Periodistas de a Pie. Periodistas de a Pie is an organization that discusses journalism strategy and is a network of support for training journalists. They teach journalists to focus on human rights perspectives in stories and also work to defend freedom of information.

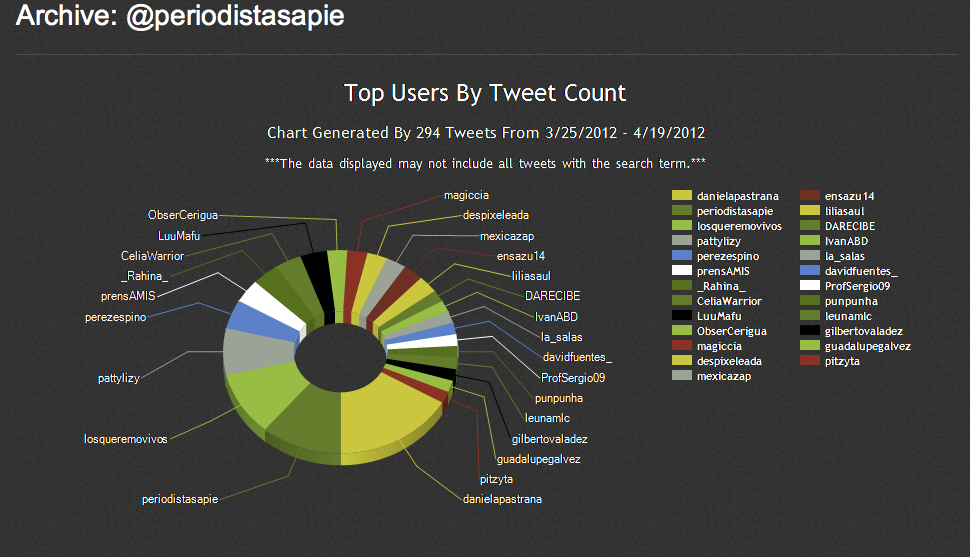

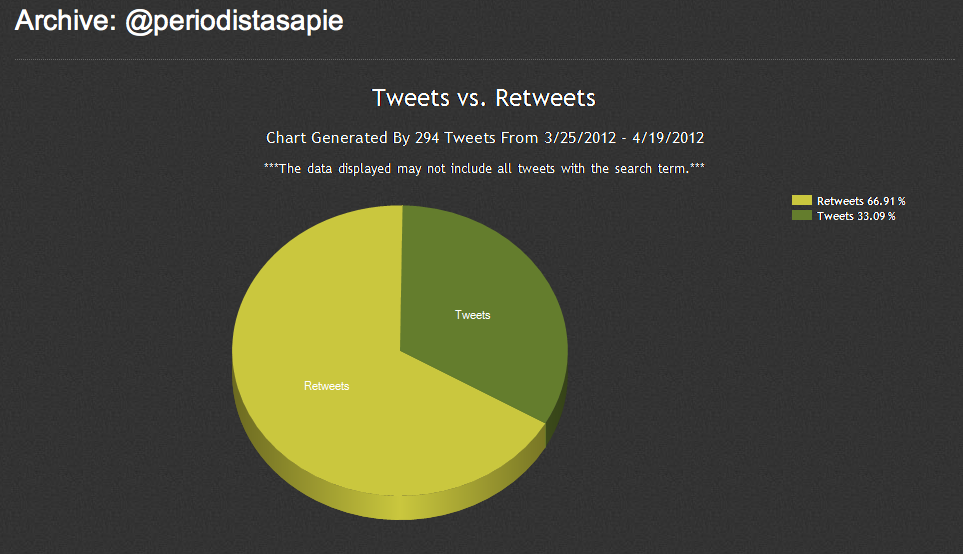

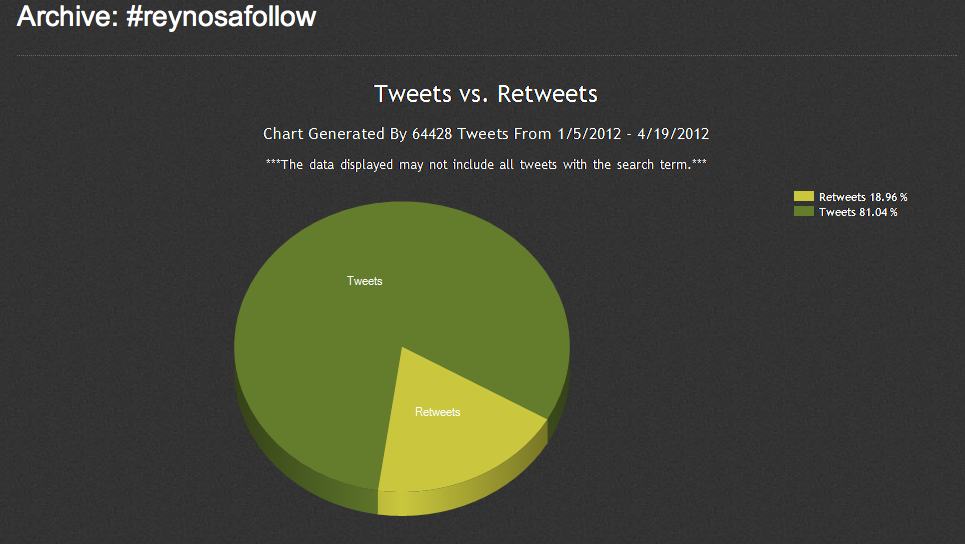

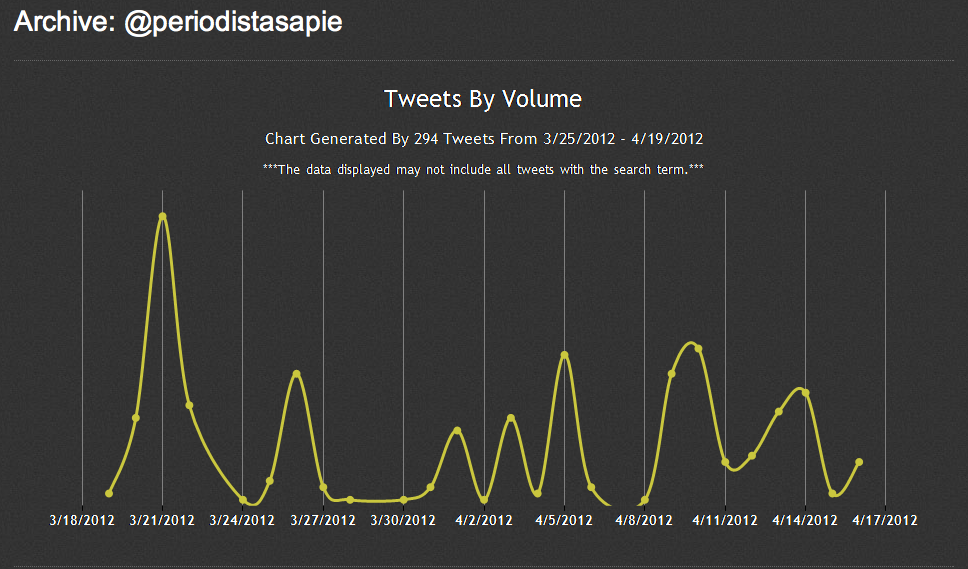

Through their Twitter handle @periodistasapie, this research tracks the top users, top words used, tweets versus retweets, and number of tweets over time connected to the organization Periodistas de a Pie. The spikes in tweets on specific days are used to target the increased conversation that is happening in the Twittersphere. Using The Archivist, this research indicates that the organization’s top users are predominantly individual journalists or organizations that are interested in the journalists’ network (Appendix B.2.1). This illustrates the point made by researcher Paola Ricuarte, that there is a small network (“cyber intelligentsia”) in the capital that does not involve concerns from the outlying areas of Mexico, where violence against journalists is actually happening (2012). The organization's presence on Twitter is mostly retweets, versus original tweets, which illustrates that the information they collect and share supports the overall knowledge of their network (Appendix B.2.2). The majority of content is not original, but it reaches far into the network. This is not uncommon for a news organization’s Twitter feed, to be the originator of content, which other users look to to disseminate information. Contrary to a news organization or specific user, a hashtag will contain more original content because multiple users use it for various purposes. A hashtag, like #reynosafollow, produces more original content but does not impact a network in the same way that an established organization does (Appendix B.2.3).

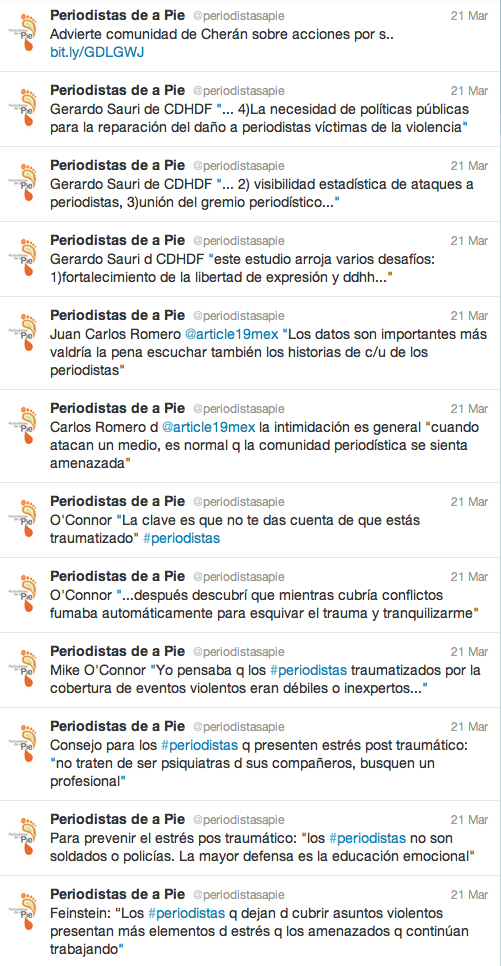

When the organization’s tweets over the past several weeks are examined (Appendix B.2.4), there is a spike in the conversation on March 21, 2012. The spike in the conversation that day was related to the need for the government to take a more active role in the protection of journalists and prosecution of their murderers. Tweets published that day indicate what the organization and journalists are actually talking about within the public sphere (Appendix B.2.5). The conversation revolves around the mental health of journalists and what steps need to be taken to support journalists who are victims of intimidation and violence. Juan Carlos Romero from Article 19 said that more than half of journalists in Mexico are bullied and threatened, and that has become normal for journalists in Mexico. Gerardo Sauri of CDHDF (Human Rights Commission of the Federal District) said that there is a need to strengthen freedom of expression, publicize the statistics of attacks on journalists, and also there is a need for public policies for the repair of damage to journalists who are victims of violence. This indicates that what journalists are actually talking about on Twitter is advocating for their protection and rights and how the government should support them.

We see the potential for media organizations for information diffusion online, particularly through the immediacy of Twitter, but whether this is actually taking place on issues relating to citizen security is questionable. The role of media in society is largely accepted as one to report on issues of public importance. But in Mexico, violence committed against journalists has ushered in an era of silence and intimidation in reporting. Mexico is currently listed by the Committee to Protect Journalists as the most dangerous country in the world in which to practice the profession, largely due to a rise in the decentralized control of drug cartels who will coerce, kidnap or kill journalists reporting on issues related to them (Lauría and O’Connor, 2010). News organizations have met this challenge by either changing their reporting tactics, such as providing anonymity for reporters, or have omitted reporting on some issues entirely--but this has brought with it an overall decline in the quality of daily news (Farah, 2012).

Contrary to the lessons learned in Colombia in the 1990s, there is a lack of cohesion amongst journalists and the federal government in Mexico to combat violence against journalists (Farah, 2012). Though attempts have been made, such as the Phoenix Project, to rally Mexico’s journalists around a strategy for reporting en masse issues of drug violence, none have been successful (Farah, 2012). Though Mexico’s Senate has proposed changes to their current policy, which would make violence against journalists a federal, rather than a state or local crime, whether it can be fully integrated or implemented is yet to be seen (Farah, 2012). The reign of impunity of violence against journalists could come to an end on paper, but because of the decentralized nature of the drug war, and the concentration of attacks on journalists within state and local municipalities, far out of reach of the capital of Mexico City, implementation of any proposed changes could prove to be an immense challenge.

There is a stark difference between the handling of violence against journalists in Colombia in the 1990s versus Mexico today. The distinguishing characteristic in this debate is that social media was not an option to create discussion or protect journalists--but the organizational network power and anonymity that can be afforded by the online realm, contrary to a traditional public sphere, presents Mexico with a huge opportunity to end the reign of impunity and better serve their audience. To this point, Mexico’s news organizations have yet to master social media tools to report on issues related to citizen security, though the internal conversation indicates that a new trend may be emerging. Social media could undoubtedly play a huge role in combatting the decentralized nature of the attacks against journalists, and the decentralized nature of the drug war in Mexico.

IV.C – GOVERNMENT

Secretaría de Seguridad Pública (@SSP_mx), Public Safety Ministry

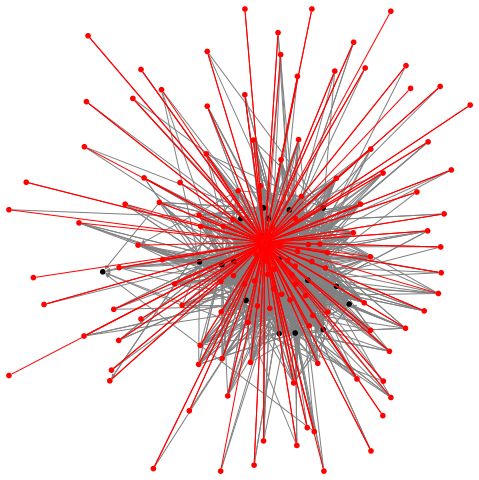

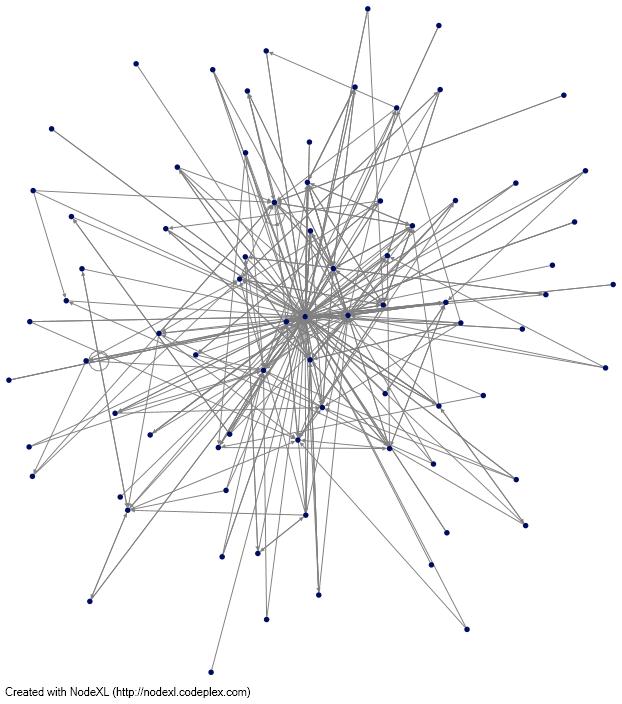

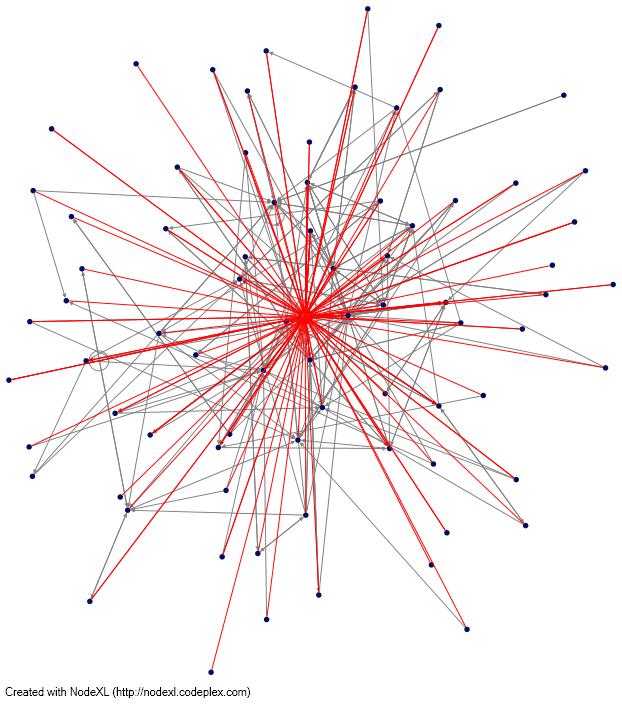

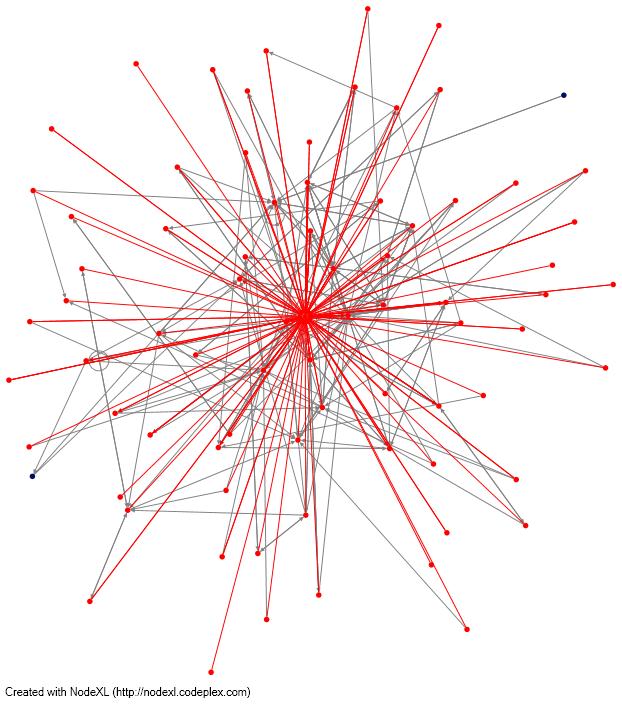

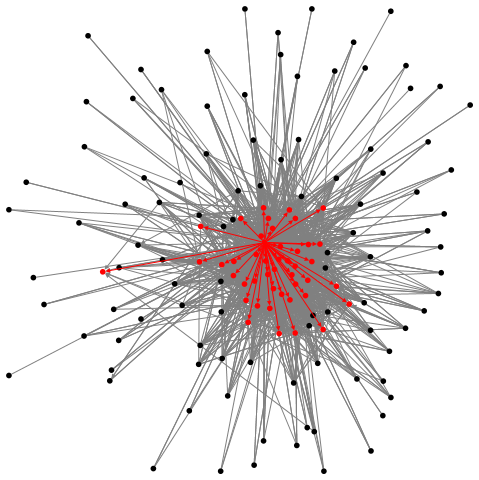

A minority of the SSP’s Twitter network connections are generated by the SSP’s account itself. The majority of connections are the result of independent users in the network. Figure C.1.1 shows the proportion of tweets generated by the SSP’s account (red) to tweets containing “@SSP_mx” (grey) in a 100-N sample of the network. More users send information to the @SSP_mx than receive information directly (Figure C.1.2). Information spreads through the network among users, who make up nodes in the network, represented by the black dots. The central node is @SSP_mx, but as several of the grey lines on the left show, some users bypass @SSP_mx completely when sharing information generated by the SSP or information about it. More lines stemming from a single node indicates that this user has a higher number of connections to others in the network.

Data on top 25 users indicates the high volume, high frequency tweeters in the space. However, these users’ proportionate dominance over the space does not greatly increase. The relatively low volume of tweets containing @SSP_mx per top user indicate that it does not take a substantial change in the number of tweets to alter a change in ranking, or to enter and leave the top 25 ranking. Interestingly, the SSP is not a top tweeter in its own network; rather, the power of this network to spread information depends on a large number of loosely connected users who have a common interest in security events in Mexico.

Between February 26, 2012-April 18, 2012, people mentioned the SSP’s twitter handle, @SSP_mx, in 10,723 individual tweets. @SSP_mx only sent 28 Tweets itself since February 26, 2012, and 715 since the creation of the account. The account had 40,478 followers as of March 27, 2012, which suggests that the high volume of SSP-related tweets is the result of people communicating about the SSP, rather than in direct communication with its Twitter account. The account is only following 43 people, most of which are government officials or government agencies, which make this assumption more concrete. Two content analyses of 1,130 tweets during two 10-day time periods shows that this discussion includes retweets of security reports, discussion about security events, and both criticism and praise of the SSP by the SSP account.

@SSP_mx receives a high cumulative volume of tweets overall, but the volumes throughout weekly cycles go high and low. This indicates that tweet volume mirrors a news cycle centering around new information related to the account, rather than sustained interest in generating conversation with the entity itself. Tweet volume dropped significantly after March 29, the day before all government-related twitter accounts were disabled due to Mexico’s election cycle. While data from the Archivist showed an approximate 3:1 ratio of tweets to retweets, the variety of attribution methods used by Mexican tweeters means that not all actual retweets, or tweets with unoriginal content found in other tweets. A 212-N sample used in our content analysis indicates that the tweet-retweet ratio is closer to 1:9.The researchers performed content analysis of tweets containing the @SSP_mx on a sample of two time periods, each spanning 10 days: February 23-March 1, 2012 and March 31-April 10, 2012. Tweets were obtained by searching @SSP_mx in the Archivist, which pulls information from Twitter, or directly from Twitter.com, respectively. These two periods were selected as they represented the most complete dataset of the tweets we had archived over a continuous time period. The first period consisted of 1,130 tweets in which @SSP_mx appeared, while the second period had 940 tweets with @SSP_mx, for a total of 2,070 tweets examined for content analysis. The @SSP_mx account was active in the February period, while it was disabled in the April period due to Mexican restrictions on promotional government material three months before a presidential election.

A small minority of sample tweets, 10 in total, was determined to be original content, meaning the tweet contained information that was not simply quoting a news story or repeating identical information about a security event. These messages reflected a range of ideas, including requests for help with a security situation, difficulty traveling, and critiquing SSP conduct. The remaining tweets contained news/incident information found multiple times that carried no attribution marks. More tweets cited a news source in April, possibly due to the SSP account’s inactivity, which forced more users to get security information from other sources. The sample suggests that the vast majority of content (95%) is not original, but rather, that the network is used to push out information about security.

The data indicates that while the Twitter network for @SSP_mx acts as a space in which participants read security information and spread this information through their networks, the “public” within this space is limited to a small portion. While the SSP’s absence from the top user slots in its own network indicates that its control over the conversation is limited, the ratio of original to unoriginal content suggests that SSP tweets about security incidents are widely circulated and make up a significant percentage of the content. The substantial drop in tweet volume after the SSP’s account was deactivated also indicates that its tweets, though few, are an important trigger in the spread of information in the network. Therefore, the SSP appears to hold an edge in content management in the space, and therefore possible influence over the topics discussed in its segment of the Mexican public sphere. However, the SSP does not participate in wider communication about its messages, nor other topics of discussion in its network, which limits its potential to be a thought leader where discourse on security does occur.

A serious limitation to the @SSP_mx’s network in terms of its potential to generate a public sphere around security issues may rest with its lack of believable appearance, one of the five key characteristics of a Hauser’s rhetorical public sphere. This stems partly from the Mexican political context, and widespread distrust of government. The legitimacy of security forces has been frequently called into question, with corruption of local police forces, and high profile cases of corruption and human rights abuses by federal security forces undermining Mexico’s drugs war over the past six years. In terms of the contextual medium in which government is disseminating information about security, the @SSP_mx network also fails to demonstrate believable appearance by using Twitter as a one-way, instead of an interactive online public sphere. Rather than retweeting or interacting with users, and users not official government accounts at that, @SSP_mx indicates that it has not taken the time to properly understand the medium, and therefore the universe in which its intended audience interact.

V. FINDINGS

The aim of our project was to research a new communicative space, or public sphere, that Mexican citizens are occupying to generate a conversation about drug related security and uncover data where the conversation is taking place. Twitter, blogs, and qualitative data is the best way to observe the changes of information flow on security measures, and create relationships between the data itself and find meaning

V.A. CIVIL SOCIETY FINDINGS

V.A.1 Movimiento por la Paz:

Movimiento por la Paz’s continued efforts to raise awareness on Mexico’s narco related violence and to bring a voice to the victims of the drug war demonstrates how civil society creates a forum to discuss critical issues in Mexico’s public sphere. Common values and goals are shared within this sphere including messages of peace, justice and dignity. As demonstrated in this report, MPJD are increasingly using social media platforms to spur community action and offline change. According to one of our interviewee’s, Fred Rosen, MPJD is addressing the issue of citizen security and violence in a roundabout way as they are not attacking the cartels or the government directly (Rosen 2012). Instead, they are sending non-violent messages with sustained hope and faith that the situation will receive the attention it deserves from the responsible parties, including the Mexican and U.S. governments. The caravan of peace throughout North America in August is yet another example of reaching out to the people via non-violent means. The movement has reached out to many civil society groups nationally and internationally and are continuously growing, contributing to a public sphere charged by hope and faith that Mexico’s security situation will improve as they are #hastalamadre with the escalated number of victims affected by the drug war.

V.A.2 BLOG DEL NARCO

Blog del Narco is transforming the way that Mexican citizens contribute to the public sphere, and communicate with each other about narco-related security. Due to corruption of the government and “autocensorship” of traditional media outlets, citizens have to rely on blogs like Blog del Narco and civil society discussions online to learn about security and narco-related crime. (Vinas, 2012) The information has become a two-way flow where citizens can provide information to the discussion, transforming this online public sphere into a place of emotional discussion and dialogue

V.B. MEDIA FINDINGS

The potential for media power within a Twitter network, to command information flow in the public sphere, is due largely to their offline identity. This clout is carried into the online realm, but journalists are as of yet unable or unwilling to use it to their advantage in Mexico. The actuality of what media organizations and journalists are discussing on Twitter is not what was expected, however, and may be resultant of the security context journalists face in the offline realm. Via social media, there is more of a conversation amongst journalists and the public about journalists themselves, and their institutions, such as how to better protect them. Rather than reporting on violence and citizen security, they are reporting on ways to enable them to report on violence and citizen security. The calls for protection, and the outlined steps to provide it to journalists, have originated outside of Mexico, from international aid and news organizations that report on the issues. We are seeing now, for the first time, an internal conversation taking shape from Mexico’s journalists and a call to action to end a reign of impunity.

V.C. GOVERNMENT FINDINGS

Generally, suggestions for courses of action to address a shared security problem were absent in the researchers’ sample for @SSP_mx, indicating that an underdeveloped, or at best ineffective, public sphere exists in the space. While a network of users have formed around @SSP_mx, the structure of the discursive space has resulted in information dissemination rather than critical engagement. Low trust in the SSP offline suggests that this online space linked to the SSP lacks believable appearance, which discourages users against active participation in a conversation about security in this space, though it is occurring in other spaces of the social media public sphere such as Movimiento por La Paz, as well as those not investigated in our research. The lack of mobilization in the @SSP_mx sphere suggests that social media is not a panacea for weak feedback loops between citizens and government; where the government is not interested in its citizens’ input, the political public sphere is severely crippled, no matter the platform on which it takes place.

V.D. MACRO FINDINGS

Social

media has the potential to be a tremendous enabling tool in Mexico’s

fight for citizen security. Social media democratizing force

enables strategic communication between governors and the governed

and could be an enabling force in the citizen security context to

connect governors, media, civil society, and individuals to

disseminate information. But this potential has not yet become

a reality and faces two distinct, and related, challenges.

● First is the issue of connectivity for Mexico’s citizens, a virtual digital divide that prevents access to technologies like social media that could be a tool in combating the drug war, and enhancing citizen security initiatives.

● Second, is the security context itself- the decentralized nature of the drug war that mirrors the technological connectivity issue, as those who are victimized are outside of the formal power and technological center of Mexico City.

Third, the idea of reciprocity and engagement are best suited to social media, where communication flows two ways. All three sectors of civil society, government, and media need to leverage their online presence to affect offline change in the citizen security context in Mexico.

V.E.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Future research in this field should focus primarily on the challenges presented in this draft—on how to connect excluded populations in rural areas where the majority of drug violence occurs, and how to create effective outreach strategies that are both sustainable and produce measurable outcomes. For example, how can the three sectors analyzed in this report--civil society, the media, and government--coordinate the exchange of information in social media networks to the advantage of Mexican society as a whole?

VI. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anonymous blogger. Interviewed by Kathleen Leasor. E-mail correspondence. February 24, 2012.

AP. “Homicidios dolosos crecen 7.9%: SNSP.” Criterio Hidalgo. 24 Feb. 2012. Accessed 8 Mar. 2012. http://www.criteriohidalgo.com/notas.asp?id=81003

Caldwell, A. & Stevenson, M. (April 9, 2010). U.S. Intelligence, Says Sinaloa Cartel Has Won Battle for Ciudad Juarez Drug Routes. Associated Press.

Cave, Damien. “Mexico Turns to Social Media for Information and Survival.” The New York Times. 24 Sept. 2011. Accessed 15 Feb. 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/25/world/americas/mexico-turns-to-twitter-and-facebook-for-information-and-survival.html?_r=1

Designing and Implementing a Knowledge Management Strategy at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency: Results and Recommendations of the Information Strategy Team. 23 Aug. 1999. Edited for the EH Knowledge Management Steering Committee to reflect EH goals. Accessed 22 Apr. 2012. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/eh/local/knowproj/docs/model.pdf.

Farah, Douglas. “Dangerous Work: Violence Against Mexico’s Journalists and Lessons from Colombia.” Center for International Media Assistance. 11 Apr. 2012.

Guevara, Miguel Angel. “Mexico: Uproar Over Twitter Law Proposed by Veracruz Governor.” Global Voices. 23 Sept. 2012. Accessed 15 Feb. 2012. http://globalvoicesonline.org/2011/09/23/mexico-twitter-users-speak-out-against-law-pushed-by-veracruz-governor/

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge: MIT, 1989).

Hauser, Gerard. Vernacular Voices: The Rhetoric of Publics and Public Spheres (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1999).

Kendzior, Sarah. “The subjectivity of slacktivism.” Al Jazeera. 5 Apr. 2012. Accessed 29 Apr. 2012. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/04/201244114223946160.html.

Lauría, Carlos, and O’Connor, Mike. “Silence or Death in Mexico’s Press.” Committee to Protect Journalists. 8 Sept. 2010.

“La (in)constitucionalidad de la #LeyGlocalización.” Human Rights Geek. 21 Feb. 2012. Accessed 15 Mar. 2012. http://www.humanrightsgeek.blogspot.com/2012/02/la-inconstitucionalidad-de-la.html

“Mexico to Release Crime Statistics.” Latin American Herald Tribune. 9 Feb. 2012. Accessed March 8, 2012. http://www.laht.com/article.asp?ArticleId=469742&CategoryId=14091

“México: A un año del surgimiento del Movimiento por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad,” Global Voices Español, March 29, 2012. Accessed April 10, 2012. http://es.globalvoicesonline.org

Miller, Vincent. Understanding Digital Culture, (London: SAGE, 2011).

Mosso, Rueben y Redacción. “Cifras de ejecutados ya, exige el IFAI del gobierno.” Milenio. 6 Jan. 2012. Accessed 8 Mar. 2012. http://impreso.milenio.com/node/9090286

Nonaka, Ikujiro. “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation.” Organization Science 5:1 (Feb. 1994): 14-37.

Nuevo Laredo en Vivo. 2012. Accessed 30 Jan. 2012. http://nuevolaredoenvivo.es.tl/

Orgad, Shani. “From Online to Offline and Back: Moving form Online to Offline Relationships with Research Informants.” ed. Christine Hine. Virtual Methods. New York: Berg, 2005

Oscar. “Cyber-Guardians: Mexican Drug War Creates New Mexican Revolution.” Instablogs. 28 Apr. 2010. Accessed 15 Feb. 2012. http://jacqui.instablogs.com/entry/cyber-guardians-mexican-drug-war-creates-new-mexican-revolution/

Phan, Monty. “On the Net, ‘Slacktivism’/Do Gooders flood inboxes [sic].” Newsday. 26 Feb. 2001. Accessed 29 Apr. 2012. http://www.newsday.com/news/on-the-net-slacktivism-do-gooders-flood-in-boxes-1.386542.

“PRI aprueba ‘Ley Duarte’; 4 años de cárcel por tuitear rumores.” Sinembargo.mx. 20 Sept. 2011. Accessed 15 Feb. 2012. http://www.sinembargo.mx/20-09-2011/43243

Ricaurte, Paola. “Our Interview with Paola Ricaurte, Social Media Researcher.” SoMe enVivo. 27 Feb. 2012. Accessed 24 Apr. 2012. https://someenvivo.wordpress.com/2012/03/01/our-interview-with-paola-ricaurte-social-media-researcher/.

Rosen, Fred. “Phone Interview.” April 16, 2012

Rodriguez, Olga. “Blogger Beats Mexico Drug War News Blackout.” Huffington Post. Aug 18 2010. Accessed 28 April. 2012.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/08/12/blogger-beats-mexico-drug_n_680942.html

Rodriguez Soto, Eduardo. “El Gabinete en Twitter, 10 meses después.” Animal Político. 28 Feb. 2012. Accessed 15 Mar. 2012.http://www.animalpolitico.com/2012/02/el-gabinete-en-twitter-10-meses-despues/

Sullivan, John P. and Adam Elkus. “Mexican Drug Lords vs. Cybervigilantes and the Social Media.” Mexidata.info. 5 Mar. 2012. Accessed 15 Mar. 2012. http://www.mexidata.info/id3288.html

Telecom Paper. “Mexico govt launches programme to reduce digital divide." International Telecommunications Union. 16 Mar. 2012. Accessed 24 Apr. 2012. http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/newslog/Mexico+Govt+Launches+Programme+To+Reduce+Digital+Divide.aspx.

Anonymous blogger. Interviewed by Kathleen Leasor. E-mail correspondence. February 24, 2012.

VII - Notes

VII – Appendices

Appendix

A – Civil Society Sector Images

1. Movimiento por la Paz (MPJD)

Figure

A.1.1: Tweet volume over time (03/01 - 04/17)

2. Blog del Narco

Figure A.2.5: Top Users by Tweet Count (03/27/12 - 04/26/12)

Appendix B – Media Sector Images

Figure B.1.1: Hashtag #mtyfollow. [NodeXL] Figure B.1.2: Image: Civil society organization @CIC within the #mtyfollow network. [NodeXL]

Figure B.1.3: Individual user, @erikam, Figure B.1.4: Network for Twitter handle within the #mtyfollow network. [NodeXL] @periodistasapie. [NodeXL]

Figure B.1.5: There is a three-step process by Figure B.1.6: Second, they

which users in the network receive information engage with a conversation

represented in images B.1.5-B.1.7. First, news with their followers. [NodeXL]

organizations

disseminate information. [NodeXL]

Figure

B.1.7: Finally, users share that information with their

followers, which results in a complete “information saturation”

of the network. [NodeXL]

Figure

B.2.1: The top users in the network for @periodistasapie are

predominantly individual journalists or organizations that are

interested in the journalists’ network.

Figure

B.2.2: @periodistasapie’s presence on Twitter is mostly retweets,

versus original tweets, which illustrates that the information they

collect and share supports the overall knowledge of their network.

Figure

B.2.3: A hashtag, like #reynosafollow seen below, produces more

original content but does not impact a network in the same way that

an established organization does.

Figure

B.2.4: Archived tweets from @periodistasapie from the past several

weeks.

Figure B.2.5: Collection of Tweets from Mar. 21, 2012, where it spikes on the timeline.

Appendix

C – Government Sector Images

1.

Additional Network Analysis

Figure

C.1.1: Information sent out by @SSP_mx, 100 N sample. [NodeXL]

Figure C.1.2: Information flows to @SSP_mx, 100 N sample. [NodeXL]